One of the Torah’s most baffling episodes, which clashes with modern cultural sensibilities, unfolds in Exodus 4:24-26. Here, right after commissioning Moses to lead the Israelites out of Egypt, God unexpectedly tried to kill him. What follows is a cryptic scene involving Zipporah, Moses, one of their sons, and their Holy God.

The story and its ambiguity

וַיְהִי בַדֶּרֶךְ בַּמָּלוֹן וַיִּפְגְּשֵׁהוּ יְהוָה וַיְבַקֵּשׁ הֲמִיתוֹ

It happened on the way at the lodging place that YHWH met him and sought to cause his death (וַיְבַקֵּשׁ הֲמִיתוֹ; vay’vakkesh hamito).

וַתִּקַּח צִפֹּרָה צֹר וַתִּכְרֹת אֵת עָרְלַת בְּנָהּ וַתַּגַּע לְרַגְלָיו וַתֹּאמֶר כִּי חֲתַן-דָּמִים אַתָּה לִי

Then Zipporah took a flint (צֹר; tzor) and cut off her son’s foreskin and touched his feet (וַתַּגַּע לְרַגְלָיו; vataga l’raglav), and she said, “Indeed, a bridegroom of blood you are to me! (חֲתַן-דָּמִים אַתָּה לִי; khatan damim ata li)”

וַיִּרֶף מִמֶּנּוּ אָז אָמְרָה חֲתַן-דָּמִים לַמּוּלֹת

So He relented from him. At that time, she said, “A bridegroom of blood,” because of the circumcision. (Ex 4:24-26)

Sometimes the Torah is too terse, resulting in ambiguity. This text is no exception. While this lack of explanatory information may in fact be intentional, it frequently creates frustration among Bible interpreters.

You should always keep in mind that if you stumble on something weird in the Bible (that does not make any sense), it is probably extraordinarily important. In other words, the oddness of any text may be there to draw your attention to it, encouraging you to linger.

From our terse text (Ex 4:24-26), it is not even clear that God sought the death of Moses. It may very well be that He sought to take the life of Moses’ son instead. The son’s name is not specified, but the most likely candidate is Gershom (Ex 2:22). Second son Eliezer appears only later in the narrative (Ex 18:3). But why would we even consider God threatening Moses’s son with death? The short answer is context.

Immediate Before and After Context

Whenever we seek to understand Biblical texts, especially one as notoriously difficult, we must take the time to examine what happens immediately before and after to see how the text fits its context. It turns out that both the preceding and following texts involve God’s firstborn son—Israel. This is significant because Gershom, whom Zipporah circumcises, is the firstborn of Moses and Zipporah.

We read in the text that comes immediately before as God instructs Moses about his coming meeting with the Pharaoh of Egypt:

22 Then you shall say to Pharaoh, ‘This is what the Lord says: “Israel is My son, My firstborn. 23 So I said to you, ‘Let My son go so that he may serve Me’; but you have refused to let him go. Behold, I am going to kill your son, your firstborn.”’ (Ex 4:22-23)

The text that follows our enigmatic passage affirms that Moses’ God is deeply concerned about the children of Israel (Ex 4:27-31).

If it is true that God sought the death of Moses’ son, then the earlier threat of taking the firstborn son of Pharaoh would now apply to the firstborn son of disobedient Moses as well.

Now that we see the immediate context, we are ready to seriously consider what transpires in the text sandwiched between the two passages just quoted.

The Elephant in the Room

Zipporah resolves the situation by circumcising her son and then touching Moses with the bloody piece of Gershom’s foreskin, declaring that after her action, Moses finally became the “bridegroom of blood for her.” It is most logical to assume that neither Gershom nor Moses was circumcised in accordance with the covenant demands of Israel’s God. Later in the Book of Joshua, the same situation repeats itself with a whole new generation of the sons of Israel. A second nationwide circumcision needed to be performed. (Josh 5:2-7)

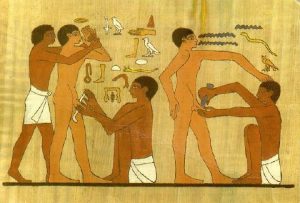

But you may ask, how could Gershom, the firstborn son of Moses, and Moses himself not have been circumcised? Several possibilities exist, but in Moses’ case, the most logical explanation is that he considered himself already circumcised. Raised in Pharaoh’s palace, Moses grew up as an Egyptian prince, surrounded by a culture where the male members of the elites were circumcised. However, his circumcision was not performed as a covenant with the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, but rather in accordance with Egyptian circumcision practice.

It is plausible that Zipporah and Moses disagreed on this matter. Zipporah may have believed that Moses should have been properly circumcised long ago, while Moses held a different view. Alternatively, Zipporah might have been aware of Moses’ desire to be circumcised correctly but knew he had been procrastinating on this important issue. Either way, Zipporah seemed to know exactly what needed to be done to avert tragedy.

To us, the modern (mostly Christian) readers, this emphasis on circumcision may sound misplaced. Why would God care so much about a physical mark? But for YHWH, circumcision was non-negotiable. It was the sign of the Abrahamic covenant for all Israelites (Genesis 17:10-14).

The penis was circumcised, not the nose or fingers, because God owned the man and his descendants. The physical sign was only given to men, but it was also important for wives to know their homes belonged to the LORD.

To be uncircumcised—or improperly circumcised—was to stand outside that covenant, a serious breach for any Israelite, let alone the leader of the Exodus. Moses was about to spearhead “Operation Exodus,” the greatest act of divine deliverance in Israel’s history. Yet probably he and certainly his firstborn son Gershom, lacked the all-important covenantal sign. This wasn’t a minor oversight. It was a serious disqualification to his fitness as God’s chosen emissary.

Zipporah’s Intervention

Enter Zipporah, Moses’ Midianite wife, who emerges as the unsung hero of this drama. When God confronts Moses with deadly intent (וַיְבַקֵּשׁ הֲמִיתוֹ, vay’vaqqesh hamito), Zipporah acts swiftly. Grabbing a knife made out of stone, she cuts off her son’s foreskin, and with it she touches Moses’ feet (וַתַּגַּע לְרַגְלָיו, vattaga l’raglav). Then she utters her enigmatic words: “Surely you are a bridegroom of blood to me” (כִּי חֲתַן-דָּמִים אַתָּה לִי, ki chatan-damim atah li). Immediately, God relents, and Moses is spared.

What’s going on here? Let’s unpack it step by step.

First, she clearly knows that this has to do with circumcision. Otherwise, she would not be able to act so quickly to remedy the situation. By circumcising Gershom, she addresses the covenantal failure in her husband. But why touch the foreskin to Moses’ “feet”? The Hebrew word רַגְלָיו (raglav, “feet”) is often a euphemism for the male reproductive organ in the Hebrew Bible (see, for example, Ruth 3:7 or Isaiah 7:20). It’s likely that Zipporah, after circumcising Gershom, symbolically transferred Gershom’s circumcision to Moses. In doing so, she declared Moses to be in the right standing with God, as if he himself bore the proper sign.

We can’t be sure of every detail in this event. After all, Moses might have been circumcised but neglected to circumcise his son. In this scenario Zipporah may have performed the circumcision of Gershom and credited Moses with doing the job he was supposed to have done. But this brings us to her words: “bridegroom of blood to me.” The Hebrew phrase חֲתַן-דָּמִים (chatan-damim) is striking. A חֲתַן (chatan) is a bridegroom, and דָּמִים (damim) refers to blood. Zipporah’s declaration suggests that circumcision isn’t just an important sign between God and a male participant. It’s also a sign that reverberates through the marriage relationship and, therefore, has relevance to the woman as well. For a woman like Zipporah, marrying a man of the covenant with YHWH meant marrying someone marked by this bloody rite we call circumcision. (Rituals involving blood were well known in Bible times, and as was the case with Passover sacrifice, they were salvific in nature). A properly circumcised man was a “bridegroom of blood” to his bride, proof that he worshiped the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. By performing the circumcision and touching Moses’ “feet,” Zipporah symbolically restores Moses to covenantal faithfulness, ensuring that he’s a true “bridegroom of (covenantal) blood” to her.

Higher Standard

God could tolerate an uncircumcised Israel for a time—they were, after all, slaves in Egypt—but Moses, the leader of the massive exodus, who would soon speak before Pharaoh representing YHWH, had to answer to a higher standard.

Let us illustrate. In the New Testament, several passages outline qualifications for the role of an elder (servant leader) in a local congregation. At a time when polygamy was a widely accepted cultural norm, an elder in a Christ-following congregation was required to be married to only one woman (the husband of one wife). Although polygamy was not explicitly forbidden for all believers, church elders were held to a higher standard, reflecting the original monogamous relationship between Adam and Eve. (1 Tim 3:2; Titus 1:6)

The qualifications for elders in 1 Timothy 3 and Titus 1 emphasize exemplary character (“above reproach”), suggesting that elders were to model the highest ethical and spiritual standards. By requiring monogamy, the early church ensured that its leaders reflected the biblical ideal of marriage, even in cultures where polygamy was acceptable. This higher standard aligned with the church’s mission to distinguish itself from surrounding cultural practices and to embody God’s design for human relationships.

Conclusion

Exodus 4:24-26, though cryptic, unveils a timeless truth: God’s covenant demands unwavering commitment, igniting inspiration for us today. Circumcision was no mere ritual but a sacred bond uniting Israel to God. Zipporah’s courageous act—circumcising her son and symbolically restoring Moses to the covenant—transformed a moment of divine judgment into redemption, mirroring the Passover’s saving blood. As a Midianite, daughter of priest Jethro, she became a beacon of faith, securing Moses’ mission to lead Israel to freedom. Her story calls us to rise above fear and cultural norms, embracing God’s call with bold obedience. Like Zipporah, we can wield faith as a flint, cutting through doubt to align with divine purpose. Her legacy inspires us to act decisively, trusting that our faithfulness can spark transformation, bridge heaven and earth, and carry forward God’s redemptive plan for the world.

Keep “Rolling Bro”! Good! Better sated: Excellent!

Thank you for your encouragement, David!

Fantastic! Amazing exceptionalism! Thank you, Dr. Eli! You are first in world-class, and to lead the way! Who is your wife, Dr. Eli??? May you both lead in God’s wisdom with faithfulness and “bold obedience”! I have been praying fervently for you and your family.

I am truly grateful and blessed by your words. I am blessed by my wife indeed.

Enlightening. Truly. You’ve given me something to think about. Thank you.

Enjoy it, brother!

Thank you very much Dr. Eli, for such a brilliant and powerful teaching.

Eric, thank you!

Thank you for explaining the passage. It enlightens my mind about those passages in Exodus 4:24-26.

Your welcome. New and exicting studies are coming soon!

Amein! I love your wife too!!! ברוך השם!

Again, I agape love your wife, too!, who gives you such wonderful insights!! I reread this article again, and it is just phenomenal, fantastic, amazing and wonderful. Thank you again, Dr. Eli and wife! — one before G-d and man!

Blessings!

You wrote an excellent comment! I can add: God knows that Moses and his family will have to take part in the Passover, but it will only be for those who are circumcised – Exo 12:48 – those who are in covenant with Him, which He made with Abram by passing between the halves of animals (Gen 15). That is why God demands Gershom’s circumcision. However, why now, i.e., in the frame of pericope 1:1-6:1? Because the four-part Passover ritual will be the four-part vassal covenant-making ritual, a ritual that God and Israel will fulfill in the events described in 6:2-11:10; 12:1-13:16; 13:17-14:31; 15:1-21 – as I have proven in my doctoral thesis. The third part of it is the passing between the halves of the Sea of Reeds, which Isaiah called Rahab in the context of this passing (Isa 51:9-10).

Dear Dr. Wojciech Kosek, My apologies, but your comment first ended up in the spam folder of the blog for some reason. Anyways, I just “freed” it from there! Wonderful comment. Thank you for this insights!

The best comment I ever read on this topic.

Ana, hi. Are you refering to prior comment but one of forum participants? or are you refering to my commentary? Blessings!

Thanks, it’s usefull. There are so many unknown things about Sephora. I’m not sure about it, but I think it’s the last time we see her in the Bible. Many years later, her father come to Moses with their sons. She wasn’t there during the exile, did he divorce her ? Why ? Why his sons don’t follow him, aren’t the first priests instead of Aaron and his posterity ? We’re talking of Moses ! Why his wife, sons are named but so absent in his story ?

Zipporah, daughter of Jethro (a Midianite priest), appears in Exodus 2:21, 4:24-26, and 18:2-6. After the mysterious circumcision incident (Exodus 4:24-26), she’s scarcely mentioned. In Exodus 18, Jethro brings Moses’ sons, Gershom and Eliezer, to him in the wilderness, implying Zipporah is present, but she’s not explicitly named, suggesting a diminished role. There’s no clear biblical evidence of divorce; some scholars speculate Moses sent her away for safety during the Exodus or due to cultural tensions (e.g., Numbers 12:1, where Miriam and Aaron criticize Moses’ “Cushite” wife, possibly Zipporah). Her sons don’t become priests because God appoints Aaron’s line (Levites) for the priesthood (Exodus 28:1). Moses’ unique role as prophet overshadows his family’s prominence, explaining their absence.

Thanks, you’re right. Zipporah is indeed quoted later, in Exodus 18. It’s the second verse that lead me to think Moses divorced her. My french Bible says about her “qui avait été renvoyée”. “renvoyer” originally means send back (where it comes from) for a letter, a package, etc. Nowadays, without context, this word rather refers to one’s job, from which he’s fired. Not in anyway a decision made to protect, but to reject ! How far are we (french translation) from the hebrew signification ?

Most translations are VERY VERY GOOD and do give most of what we need, but they do not exchance learning the original languages (this is a life long process).

That women asked a good question.

And your answer ‘Moses unique role as Prophet overshadows his family’s prominence.’

What role would his children play as adults?

And Samuel’s mom giving her son away I suspect around 2. Even that is generous by today’s standards. ( After weaning)

Sorry off topic but suddenly questions about mom’s and children arise. Thank-you. Blessings 💞🙏 ( A follower of Jesus) I may add your answer on my X but I will add your name.)

Dale, hi! I am not sure I followed everything in your comment but perhaps others did. Blessings!

I do enjoy it when someone sheds light on the more enigmatic portions of scripture. It makes for interesting and thought provoking reading.

Nicole, let’s keep thinking on this and other topics together!

Beautiful.

Blessings, Frederick!

As always, a well informed discussion of a difficult question. Thank you

This blog specializes ONLY in difficult topics and texts :-). We let others deal with everything else :-).

How do we relate the concept of the “omniscience and unchanging nature” of the Father with scriptural episodes where we are told that He “intended” doing something but then changed? These expressions seems contradictory?

Here is a great explanation from my longtimeOld Testament seminary professor, Dr. Richard Pratt – https://thirdmill.org/magazine/article.asp/link/http%3A%5E%5Ethirdmill.org%5Earticles%5Eric_pratt%5ETH.Pratt.Historical_Contingencies.html/at/Historical+Contingencies+and+Biblical+Predictions

Thank you very much for your attention I shall read with due attention.

I think that a key is what is meant by, “The Lord met Moses”. The narrative does mention a visitation by an angelic messenger, a Theophanie, or God’s presence as it appears on Mount Zion. The most likely explanation is that God spoke to Moses. We then learn that the Lord is about kill Moses and Zipporah immediately, almost robotically, knows exactly what to do. How did Zipporah know what to do? Moses must’ve told her what The Lord had told him or the message must’ve been audible and she was present. But what was the message from the Lord and why is it missing from the narrative? If Moses had not been properly circumcised, Moses may have found it embarrassing and did not see a need to include it.

Thank you for your comment, Mike.

Wow Dr. ELI. What a profound teaching! Thank you so much for bringing these biblical stories in the original Hebrew text to us. Excellent! God bless you, your family and ministry.

God bless you, Sylvia for such an encouraging feedback! I am encouraged to research and write more.

Very profound, interesting & confusing. Would God really kill Moses, the most humble man on Earth, chosen for a long & very special mission, the only man to see & speak with God personally, like friends?

Why couldn’t God say “ you need to circumcise your son?”

Remember, it could have been Moses who was not circumcised. (See the article). Gershom was not the main problem, I think. Moses was.

Thank you Eli for a very helpful and facinating insight into this passage

Lionel, thank you for your kind words!

Thanks for answering, however Moses was likely circumcised before he was put in a basket at 3 months. Egyptian priests & royalty were circumcised too.

If I were a parent of Moses and I knew that there was a decree to kill Hebrew baby boys, I would not circumcise him; this will give him the best chance for survival. But that’s me.

Thank you for your insightful analysis of Exodus 4:24–26, where you suggest that it is not entirely clear whether God sought to put Moses to death or rather his son. This interpretation opens up a particularly rich field of reflection, especially concerning the identity of the child involved and the role played by Zipporah in performing the circumcision. Allow me to raise two questions in order to deepen this discussion.

Thank you for your comment!

In Exodus 4:24–26, if we assume that it was Moses’ son whose life was threatened, how should we understand Moses’ apparent passivity in this episode? Exodus 4:20 specifies that Moses took “his wife and his sons” with him on the journey to Egypt. As a father, he bore direct covenantal responsibility in relation to the Abrahamic command (Gen 17:10–14). Why, then, is it Zipporah rather than Moses himself who performs the ritual act of circumcision at this critical moment?

I would suggest that Tziporah was his EZER KENEGDO (like Eve for Edem). Ezer is usually translated as a helper, but really it is an interventionist agent willing to die and kill for you.

The narrative in Exodus 4:20–26 does not specify the name of the son who was circumcised, but the text makes clear that Moses had taken “his sons” (plural) with him. Exodus 18:2–4 later identifies them as Gershom and Eliezer. If Gershom is often assumed to be the child in question, on what textual basis can the possibility be ruled out that it was Eliezer? The injunction of Genesis 17:12 required circumcision for every male child, not only for the firstborn. Would it not therefore be reasonable to reconsider the possibility that Eliezer was the son circumcised in this episode?

Yes, it is possible, Pastor Julien! It is very unclear text.

A really good article, explaining a rather obscure passage.

However, it does leave one unanswered question:

Moses was born in Egypt and stayed with his parents for a period of time—possibly several months.

During this time it is quite feasible that he was circumcised in accordance with the scriptures and hence a part of G_d’s covenant.

It may also be that Pharaoh’s daughter saw the baby had been circumcised and hence recognized him as ‘one of the Hebrews.’

(I don’t know when Egyptians were circumcised, but it was unlikely to be on the eighth day)

Donald, I agree my explanation is a hypothesis and a possible reconstruction. But that’s how it normally is in humanities vs. exact sciences. Moses was likely uncircumcised because his parents tried to save him from getting killed as a Jewish boy.

I thank God for every transformational change (death & rebirth/upgrade/growth) that serves Gods will always, bridging heaven & earth, in the name of Jesus. Amen. Shalom. ❤️✝️🙏

Amen to that!

❤️✨🙌

Thank you for this and all the other so interesting articles in this blog. What strikes me is that the patriarchs and Moses each had a very intense, mysterious experience with God: Abraham and Isaac in the story of the offering of Isaac (Gen 22), Jacob, who wrestles in a mysterious way with God (Gen 32) and now Moses and Zipporah with another mysterious experience with God. All these are different stories, but it seems to me that being chosen by God to fulfill an extraordinary task requires a test of loyalty, which includes an extraordinary preparation through an intense experience of God.

Ingrid, this is a very good point. It would be interesting to see if all other key biblical figures had something like that too Perhaps this is a study you can undertake and see if your hypathesis holds water. It may very well!

Since Moses was 3 months old when he was placed in the river, and since Pharaoh’s daughter recognized him to be a Hebrew, my inference is that Moses was already circumcised as was the custom. It is possible that she recognized his clothing, but most likely one look at his “feet” would have confirmed it. It seems like from the Egyptian hieroglyph that it was boys were circumcised as a rite of passage into adulthood.

There are most certainly other interpretive options (than the one I am suggesting as the most likely). However, the fact that a baby was floating in a basket (uncircumcised) may have been proof enough that it was in fact a Hebrew baby boy (parents did not circumcise him in order to save him).

I really enjoy your work. I find it very informative.

Thank you, Lisa. Spread it around!

Thanks Dr. Eli for unraveling this odd story, and sharing your knowledge from a Jewish perspective and knowledge of the Hebrew bible and language. Reading about this account in the King James version left me perplexed. In the past, me reading from the King James version left me with a bad picture of God in this incident. You do a good job of tackling this difficult scripture.

The King James Version is one of the best Bible translations in that it seeks to capture Hebrew poetry, among other things. It is not perfect, and it has its weaknesses, no doubt, like all other translations. There is a great talk out there called God’s Secretaries: The Makings of King James Bible.

Thank you for this. First time I have understood what this verse meant.

Let’s keep thinking together.

So awesome

Thanks Dr

Thank you, my brother!

Thank you very much for this beautiful and informative article.

God bless you and your ministry .

Thank you for your encouragement, Sara!

Very profound and it brings to mind, courage. How we need to have courage to carry the mantle of YHWH

Indeed, Terrence, we do!

But surely Moses would have been circumcised on the eighth day – he was kept hidden for a lot longer than that after all. And Pharaoh’s daughter immediately recognises him as a Hebrew baby presumably because he was circumcised, which the Egyptians did but not at that age.

You are right: “presumably.” However, I have already mentioned this in other comments. But most likely, they did not perform the circumcision to give baby Moses (remember, that was the name he was given in the Egyptian court) the best chance they could to survive. There is another way that Pharaoh’s daughter could have known that it was a Hebrew baby. She heard about the decree to kill all Hebrew baby boys and connected the dots (finding a baby in a little floating basket). But moreover, you still have an unexplained problem: if Moses was circumcised and Tziporah circumcised his son, why did she take the foreskin and touch the “feet” of Moses, saying, “Now you are the bridegroom of blood to me”?

Thank you for solving this mystery of mine.

Let’s keep thinking God’s thoughts after Him, together.

It was the 4th gen after Yisra’el, to walk out of Egypt. I don’t believe they had forgotten to circumcise the males on the 8th day. A covenant contract to raise the child in the way of YeHoVaH.

YeHoVaH only calls Yisra’el His people, and every foreigner who joins Yisra’el is grafted into the vine. The foreigner is now considered Yisra’el. This newly grafted in member of the body, sheep of the one flock that Yeshua has brought into the fold (Jn 10:6), then has the grace period of learning Torah, with the requirement of Acts 15:19-21. Once one learns Torah, then they keep it all, including circumcision. My thoughts on your conclusion.

Shalom

Kindly refer to my other comments about the same thing. It had nothing to do with forgetting.

Shalom Mr. Ely:

I always read your messages, but I would like to get the impirtan contexto in YouTube, your contribution it’s excelente.

See U soon

Thank you so much, Patricia!

Thank you for this teaching which has opened my eyes to a whole new story of the Exodis. Without the wisdom of Ziporah, Moses would not have been able to lead Israel out of Egypt. Wow, now this is what I call real bible study!!!

Blessings, Vivian! Girl power! 🙂

Moses was most likely circumcised on the eighth day, since he spent the first three months in the house of Levi, and this may be the real reason why Pharaoh’s daughter recognized him as a child of the Hebrews as soon as she saw him. Therefore, it is unlikely that Moses was circumcised by the Egyptians. However, the observations made in the article about Moses’ wife and about God’s covenant are valuable.

Please refer to my responses to similar comments. Blessings!

Thank you for continuing to send out your inspiring teachings! I love how you bring depth to our understanding by explaining the Hebrew meanings. Our churches in America do not clarify enough, and thus, we lose the intent of what God is doing in the Bible and leave with too many questions and doubts about God. Your teaching brings light and beautiful revelation to God’s character. You help us to realize how amazing our God truly is! Jesus bless you!!

Thank you, dear Linda!

Great insides. Your explanations shows me two things – the Lord wants to have a covenant people and for this reason He has given the specific authority or priesthood (Hebrew 5:4) to perform the binding covenants – circumcision done by not authorised Egyptian was not accepted -. It is nice to see that Paul taught exactly this to the Hebrews (Hebrew 5-10). It seems that the law of circumsicion was replaced by baptism – the new covenant – but in today’s world where is the respective authority, acceptable by the Lord? It seems that we have many “Egyptian baptisms” today. Nevertheless thank you for your great insight in Moses circumcision – respectively in the Abrahamic covenant and covenant of the First Born.

Louis, thank you. Your observation that circumcision has been replaced by the Jewish water ceremony known as baptism in Christian circles needs more nuance, in my opinion. I think that is true in the case of the nations, but in the case of Israel, I think circumcision is an internal sign that now runs parallel but does not replace the Christian baptism.

The covenant of Circumcision – of every male child’s foreskin when the child became 8 days old – was originally instituted as a sign, token and reminder for the believers of, that the age of a normal person’s personal accountability before God is 8 years. Thus, all children, who might die before they reach this age of accountability before God, will – following their resurrection – receive their salvation in God’s celestial kingdom of Glory.

How did we get to 8 years as the age of personal responsibility again? Perhaps. But how?

I am not a Hebrew Scholar and always wondered if God only wanted 8 day olds circumcised not necessarily anyone else. Just a thought.

Thanks for your comment. Please, rephrase your question. 🙂

Moses wife Zipporah was a righteous woman in many respects the remedy she employed spoke volumes about her knowledge and faith🙏❤️🙏

Indeed.

If Moses was hidden for three months after his birth (Exodus 2:2) there was adequate time for him to have been circumcised according to the Law. Why do you think he was not properly circumcised?

Please, kindly see my comments above in response to others. I adequately explain why this is a strong possibility.

Circumcision is a non-lethal form of blood sacrifice. It also represents the transfer of one’s own narrative to G-d’s grand narrative like Abraham being willing to sacrifice Isaac: this was Abraham releasing Isaac as a person within Abraham’s own narrative and “binding” Isaac to G-d’s narrative by doing so, Isaac did not have to die here, Moses’ son was taken from Zipporah’s narrative and put into G-d’s by the circumcision by touching Moses’ feet, Zipporah was putting the responsibility of the boy’s destiny on Moses.

I like it a lot! Not sure how true it is, but it could very well be. Thank you for sharing.

Interesting topic! Haven’t heard of Moses’ “feet” being some other organ, but it makes more sense in context with the story. (Also heard about so-called “feet” in Ruth’s story). Given that circumcision was pretty common during that time, I’d think that God would go for a different type of ritual to distinguish the Israelites. Could this practice have come from an ancestral practice that was sustained in different cultures? I’ve read that the Jewish circumcision tends to cut off my flesh than other practices (particularly the Egyptian). How does cutting off more flesh become more relevant or bond to God’s covenant compared to other pagan circumcision rituals? Thanks for your insight!

Jasmine, hi. No, circumcision was not common. It was practiced in Egypt but only by elites. The purpose of circumcision was not to set the Israelites apart from other people (or else they would have to constantly be nude); rather, it was a covenant with God to demonstrate that their children and future (the most significant “thing” in their lives) belonged to the LORD, which is why the male organ is in charge of creating future generations. The message of circumcision is that the LORD owns posterity.

The reality of Zipporah dawning understanding of God’s standard for leaders clearly places Moses under God’s microscope, mirroring him as a leader that must meet God’s covenantal standard. But Zipporah’s bold faith transformed not only her son but also a husband who became Israel’s great leader. This raises the question, “Where does our faith rest in the modern world?”

Thank you, Paulette!

well articulated revelation God bless you

Thank you, Daniel for writing and encouraging!

Another great commentary! For as many times as I’ve read this passage, it always piqued my curiosity that Moses’ circumcision might have been an “Egyptian thing,” where they (historically) would have removed only the tip, making this a partial circumcision. If that’s the case, would this have been an ‘invalid’ circumcision that doesn’t harmonize with Genesis 17? Interested in your thoughts!

It is difficult to know with certainty. This is a good question to ask: Is a person who was circumcised in an American hospital at birth considered biblically circumcised? The answer is probably no.

Thank-you Dr. Eli! Your explanations add so much insight to the Bible verses that I would have never known the underlying meanings had you not explained them in depth.

Mindy, yes, we need to always look for context to understand the text; otherwise, we will impose new meaning on it.

Eli,

In the above article you use YHWH two times and then twice YHVH. You may want to pick either one and use it throughout for consistency. Just a thought.

Colleen

Colleen, thank you so much! Fixed the inconsistency.

Thank you. This has been my question and i am privileged to find that you have helped answer even before i had the time to ask directly. Am grateful to find answers to too many scripture questions i have on your blog.

Understood her action to her elder son and then to her husband Moses, thank you for your interpretation.

Blessings and peace!

Thank you for the insights. But if Moses stayed with his parents for three months before being floated down the river, as stated in Scripture, how can you assume he hadn’t been circumcised on the eighth day?

Janet, hi. The answer is simple: they knew that it ALONE may save his life. That was their plan and it worked.

This is very great.

I’ve been inspired by this revelation

Blessings!

JPS Exo 2:1 And there went a man of the house of Levi, and took to wife a daughter of Levi.

Exo 2:2 And the woman conceived, and bore a son; and when she saw him that he was a goodly child, she hid him three months.

Assuming Moses’s parents circumcised Moses to be a part of Abraham’s covenant seems reasonable to me. As circumcision is to be done on the eighth day, hiding him for 3 months would allow enough time, to not do it would be disobedient. So I think it is just Gershom being circumcized. Thoughts?

I think it is possible, but it is no more likely than what I suggest. 🙂 When we do reconstruction like that, we deal with possibilities and plausibilities, not with certainties :-). Drives some people crazy :-).

The entire premise is flawed; How can an Almighty God “try” to kill a mere mortal and fail? If you really consider the background given you will come to realise the real reason the angel was there, and perhaps even realise the comparison between Abraham and Moses. I am surprised at the ready institutionalised acceptance of narratives like this without a single question being raised…

It’s amazing how people can sometimes say a lot and nothing at the same time. Please, argue and make your case. We will consider.

Dr. Eli, thanks for the response. I note that you did not address the issue of whether it is conceivable that God could fail to kill a human he wished dead; Based on the covenant that no uncircumcised male may enter the Covenant, I posit that the angel was there to kill the child if he remained uncircumcised, and Zipporah resolved the matter when Moses refused to do so. The contrast between Abraham and Moses is stark here, and since Moses remained disobedient to the end, even risking his son’s life, if the angel was there to kill him for that reason then Moses should be dead. It also explain Zipporah’s remarks to a husband that had endangered their son’s life.

Tony, thanks for your reply. I recommend you read this very carefully. We can then continue the conversation offline if you wish – https://thirdmill.org/magazine/article.asp/link/http%3A%5E%5Ethirdmill.org%5Earticles%5Eric_pratt%5ETH.Pratt.Historical_Contingencies.html/at/Historical+Contingencies+and+Biblical+Predictions

Thank you, Dr. Eli. I am grateful for the reference you provided, and will read it carefully and consider the contents thereof.

Thank you for this. I always thought Zipporah’s reaction toward Moses was because she was of pagan background and angry that a g(G)od would demand the cutting of flesh as a means of identification of his faith.

No, she is a positive agent in the story.

This was an excellent explanation!!!

Thanks, Kris!

Thanks for this insight it has helped me acquire knowledge over this I have been asking myself why God wanted to kill Moses and yet He is the one who told him to go and deliver His children from bondage. But now I have some insight thanks.

May God bless you aboundantly

Thank you so much!

This is beautifully explained. The circumcision makes sense now.

Thank you Dr. Eli for sharing.

May the Lord bless you!

This teaching talks about PURITY and ORDERLINESS Moses knows he was sent on e mission that is so serious and challenging, he needs to have be very careful to watch before going to deliver the message God Almighty sent!

Indeed.

Thank you Dr Eli. I will review the passage in Exodus to remind my self of it and the context. I am however very grateful for the illumination i got on the reference to “feet” in Ruth 3:4. I have always wondered about this but i cant recall ever researching it because up till now I still had questions. Thank you so much. It makes sense now.

Hi, Ann! Uncovering feet as sexual encounter is a strong interpretive option (in Judaism marriage could be valid formally or informally). However, this is not the only option.

Beautifull, thank you very much.your depth of the Bible is great and help to deepen our faith.

Let us grow!

In the state Moses was in, God could not send him. The circumcision he bore was a covenant with the gods of the Nile. Zipporah’s intervention must have changed the situation. Through a new covenant, the circumcision of Moses’ son in his favor.

Dans l’état où se trouvait Moïse . Dieu ne pouvait pas l’envoyer . La circoncision , qu’il portait, était une alliance aux dieux du Nil . L’intervention de Sephora a du changer la donne . Par une nouvelle alliance , la circoncision du fils de Moïse en sa faveur .

We don’t know if the circumcision he likely received as being part of the Egyptian elite had to do with the gods of egypt. PErhaps, perhaps not. But it was certainly not a covenant cut with Israel’s God. Hence, he needed to be circumcised truly.

What you said sounds more like someone backtracking on having to retreat or take back said something that shouldn’t have been said or came out wrongly. To believe that the Scribe copying the text inserted the verse in the wrong place or that the scribe that was pasting several scrolls together in one long scroll and pasted one of the shorter scrolls in the wrong order makes more sense.

There is no evidence of scribal insertion here, Albert. Perhaps you know of something. Please, advice.

I’ve been wondering about those passages,now your explanation makes sense.

We all have been for many years.

There’s a Biblical school of thought that the Pentateuch originally consisted of 4 independent traditions namely the Yahwist, Elohistic, Priestly, and Deuteronomist tradition that was later merged together to form 1 unified tradition forming the Pentateuch of today. In this effort to unite the 4 traditions it is easy that some verses had been accidentally edited out or placed in the wrong sequence when the unified tradition was written as opposed to keeping them separate like in the NT Gospels. I suggest the possibility that the Exodus verses 4: 24 -26 might just be one of these verses that got scrambled when the united tradition was written down.

I don’t like that theory, so it is challenging for me to accept this argument. Could it be? yes. Is there any evidence for it? No. But most importantly, Albert, there is no reason for it; the text reads very well within its context once it is properly understood.

Zamečateljno brat Eli.!

Thank you, Tomislav!

I thought that Moses would have been circumcised at eight days old, in the family home. I had also thought he might have been about three months old when his mother made the basket and laid him inside it to float in the river. Amazing trust, because crocodiles would have smelt a meal.

About circumcision of Moses you are correct IF THERE WAS NO THREAT TO LIFE. Historically many Jewish parents withheld circumcisions if they thought it would endanger their kids.